Zuck Park: A Millcreek Legacy

A verdant legacy lies above Lake Erie in northwestern Pennsylvania. That is Zuck Park, located in Millcreek Township, adjacent to the city of Erie. This 20 acres of former farmland was gifted to the city by its namesake in 1925. After six decades of development, declines, and revivals of a property outside its city limits, Erie officials deeded the property to Millcreek in 1987. A deep dive into historic digital issues of Erie Daily Times, revealed that perhaps no park in Erie County has a history more rich, and dramatic, than Zuck Park.

The Gift

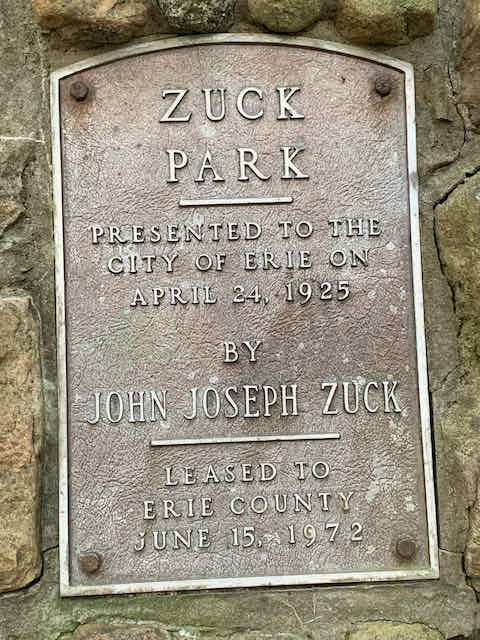

John J. Zuck (rhymes with book), a descendant of 1801 Millcreek settlers, inherited a portion of the family’s original acreage. His 100-acre farm, located between 38th Street (once Knobloch Road) and Grandview Blvd., was bisected by Zuck Road. In 1925, Mr. Zuck offered 20 acres of his land to the adjacent city of Erie, with the caveat that it would be used forever as a free public park and recreation space. The deed also stipulated that the park must be named the John J. Zuck Memorial Park and that a bronze tablet honoring the family must be placed in the park. Today, there is a large stone monument on a pathway in the park with wording that resembles the wording stipulated on the original deed.

Photo credit: James S. DeDad

Why did Zuck offer the land to the city of Erie and not to Millcreek, where the land is located? Apparently, he and many others figured Erie would eventually annex this section of agricultural Millcreek as it had already annexed five portions of the township from 1866 to 1926. Instead, Millcreek developed dramatically on its own.

The fact that the city accepted Zuck’s offer, even though the park was not inside city limits, was not without precedent. The city already owned several other parks and even a golf course outside of its boundaries.

Clinton B. Higby, John Zuck’s attorney and friend, said at the time, “This park is most appropriate in its location, providing as it does for the southwestern part of the city, for those who do not wish to go to the lake’s edge, but prefer an inland place for that rest and recreation which is always a fit and proper part of the life of the people.

Interestingly, not even a year after his initial gift, Zuck wrote a will that bequeathed the remainder of his farm, 80 acres, to the city, along with monetary gifts totaling $90,000 to Allegheny College and Edinboro Normal (now university). Unfortunately, Zuck died suddenly at the age of 79, before 30 days had passed from his signing of the will.

Pennsylvania law stipulates that a will is invalid if the testator dies within 30 days of writing it. This meant that Zuck’s next of kin, his seven first cousins, became the beneficiaries. The 80 acres, which would have made Zuck Park the largest park ever owned by the city, were instead sold off piecemeal over the decades that followed.

Creating Zuck Park

In September of 1931, six years after Erie accepted the Zuck gift, the Great Depression had thrown many families into poverty, and winter was coming. The Citizen’s Relief Committee and Parks Director W.D. Kinney issued permits for destitute families to cut down trees in Zuck Park for heating their homes. Two weeks later, the program ended with 60 families having been issued permits.

Some of present-day Zuck Park’s unique features date back to the Great Depression. In December of 1933, the Civil Works Administration (CWA) had 79 men working to “repair” Zuck Park. Landscaping and grading continued over the next several years, with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) funding most of the cost and sweat equity.

By 1938, Zuck Park had become a regional attraction, offering picnic tables and shelters for 150 people, playground equipment, a rustic bridge across a pond (no longer there), and pathways through the forest of pines, spruce, maples, and other native trees. Many of the stumps from the trees that had been cut down for wood in 1931 were transformed into rustic seats and concrete tables were placed on some of them.

Rustic pergolas, gates, walks, and play equipment were made onsite or in the one-room schoolhouse across the street. Teeter-totters, swings, and other equipment were installed “with safety in mind.” Of course, playground safety standards were quite different in those days and a few injuries were reported in the Erie Daily Times–not just involving children. In 1937, a 27-year-old man became dizzy on a swing and was knocked unconscious when he fell. In 1942, a 17-year-old woman fell from a swing while playing at Zuck Park and received a cerebral concussion. Playgound surfaces are much more forgiving today.

Throughout the many ups and downs of Zuck Park, most of the structures built by the WPA workers remain. The stone entrances to the park attract attention themselves. An octagonal wayside building, once intended for a drinking fountain, still stands, as does the well pump house just north of the modern restrooms. On a path leading to the east side of the park stands a tall chimney-like monument to the man who donated the land to the city, John J. Zuck.

In its early days, Zuck Park was also praised as a refuge for migratory birds and a haven for those that remained in winter. Nearly 800 birdhouses hung from trees. Brush piles and refuges were provided for both birds and other animal life. More than 50,000 flowering plants added beauty to the woods.

In July of 1940, Harry Engh, president of Penna Telephone Corp., donated a 65-foot flagpole. Parks Director Gale Ross purchased a flag for it. The cement base still exists near the south parking lot today.

Of all the public servants and civic volunteers who cared for Zuck Park over the years, William Hamilton, a retired businessman, is the person responsible for developing Zuck Park both as a park and as a wildlife sanctuary. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Hamilton devoted himself to the improvement of the park, acting as its advocate and supervisor. Of note was his multi-year project with the garden clubs that created a massive rose garden on the grounds. Many garden club meetings, church and civic group picnics, and family reunions were held at Zuck Park over the next few years.

Zuck Park’s First Decline

The WPA money for the park ran out before the city was back on its feet after the Depression, and city officials said there was barely enough money to maintain the parks within its city limits, let alone one outside of them. From newspaper articles at the time, it seems that as many city residents and organizations used the park as those from Millcreek.

In 1941, the city transplanted all of the roses bushes from the Zuck Park garden that Bill Hamilton had created, promoted, and tended to Glenwood Park. There had been several cases of significant vandalism, which destroyed parts of the garden. City officials blamed the lack of WPA workers to guard and keep up the park.

With the city not investing money or manpower into the park anymore, it didn’t take long for it to fall into neglect. Youth gangs harassed park visitors. Millcreek Township started prosecuting people who dumped their trash in the woods. Of the few picnics being held at the park anymore, some ended up in drunken brawls.

In 1950, the local Girl Scouts organization asked city council for a long-term lease on Zuck Park, described as having been improved during the Depression, but since abandoned. They wished to use it as a camp. Although the Girl Scouts had votes of confidence by civic groups, the request was not granted. To do so would have violated the terms of the 1925 agreement, in which the city agreed that the land would be used as a public park.

In August 1953, an Erie Daily Times columnist asked, “What ever happened to Zuck Park, the plot of land going to seed in southwest Erie? The onetime flourishing park is fast being taken over by the jungle.”

Civic Group and Youth to the Rescue

In 1957, the local Sertoma Club (since disbanded) announced that it would create and maintain a recreation site for public use at Zuck Park. The five-year plan included building picnic tables, fireplaces, and recreational equipment. The female arm of the organization, La Sertoma, volunteered to beautify one of the entrances. Millcreek police chief, Barney Moran, directed his officers to patrol the area.

The local Boy Scout organization helped Sertoma in the cleanup efforts. They cleared diseased trees and saplings to relieve crowding of large solid shade trees and planted more trees. They also started holding “camporees” in the park that involved troops from the region, reviving the park with activity again.

In 1958, 400 Girl Scouts met at the park for a scavenger hunt. Many community groups, churches, and clubs were picnicking at the park again. The local chapter of a musicians’ union held several free concerts there.

The Sertoma Club had reclaimed Zuck Park from what was described as a deserted, trash-covered area into a usable park. The members added outdoor lighting, a playground, ballfield, water well and pumping system.

A Second Decline for Zuck Park

Although softball and baseball were being played on the east side of the property, by 1963, Zuck Park was sliding into another decline. The county commissioners, who had in the past granted funds to the city for Zuck Park, removed the park’s yearly allocation from its budget. No one complained, so it wasn’t added back into the following year’s budget.

In 1968, Mayor Louis J. Tullio suggested that the park be sold to Millcreek Township, which had offered $60,000 for it, with plans of building a school there. Tullio remarked that the park was, “. . . a dense woodland. . . littered with beer cans and debris.” He said that it had, “become susceptible to criminal activities to the point where it has become a matter of concern to the neighbors and Millcreek Township Police Department.”

City Council Member Robert Brabender was vocal in his opposition to the sale. He said, “The deed clearly states that this land is to be used solely for recreational terms forever.”

After the city decided to keep the park in a 4-3 vote, Millcreek took legal action against the city to force them to clean up the park. The next day, a clean-up crew from the city was seen there.

A Second Revival for Zuck Park

In 1971, Zuck Park received some needed attention when the Boy Scouts entered into a one-year agreement with the city for leasehold rights and assumed responsibilities for the park. During cleanup, Millcreek Township provided the use of its trucks. The public would continue to have free access to the park.

By summer of 1972, a lease had been drawn up between the city and the county. County park and recreation director, Pete Russo, reported in August that fencing and lighting had been installed. Fallen trees had been cleared and plans were in place for a softball field, horseshoe pits, and volleyball courts.

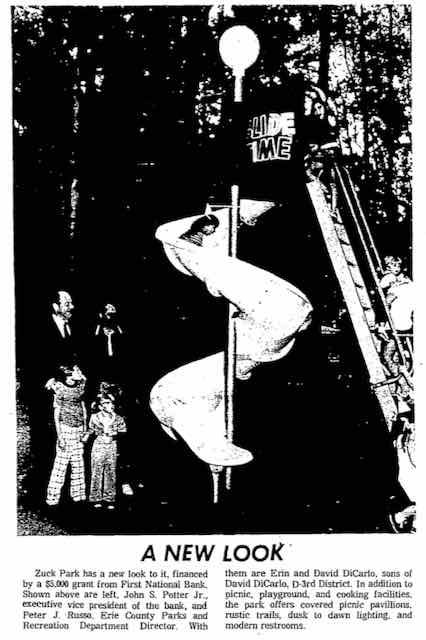

That fall, the First National Bank of Pennsylvania was opening its new downtown seven-story headquarters and as an associated project, gave the county a $5,000 grant for a permanent softball backstop, “elaborate” slide, picnic tables, permanent grills, benches, and a merry-go-round. Two years later, the work was complete and First National held a luncheon at the park to celebrate.

A Third Regression for Zuck Park

After a ten-year relationship, in 1982 the county quit its lease with the city, again leaving the park an orphan. Lou Tullio then asked Millcreek to take park operations, stating that the city residents got little use out of the park. In December of 1983, the Millcreek supervisors voted 2-1 not to take over maintenance of the park citing the lack of funds to take the expense.

In May of 1984, vandals broke the globes of the lights and knocked several standards off their bases. Only one fixture was left standing, but its globe was destroyed. The park had once again fallen into disrepair.

The Greek Orthodox church wanted to buy the land for a church in 1986, but the city said no because the deed stated that the land had to be used as a park forever. Eugene Pacidi, city solicitor, mentioned that previous court rulings allowed such a sale. A.B. Zuck, a family member said, “But, once you start selling off a chunk here and a chunk there, pretty soon not much of a park is left.”

When a young boy fell from the top of the sliding board and his mother asked that the slide be removed, city officials made an unfortunate decision. In May of 1986, the city closed the park because it said it could not acquire liability insurance on the park. It not only closed the park, but it also dismantled all the playground equipment and padlocked the gates. Because the slide that First National Bank had donated was so firmly cemented in the ground, the crews sheared off the metal support at their bases, destroying the slide in the process. The other equipment was placed into storage.

Revival and Resolution

John J. Zuck’s grandnephew, Clark F. Zuck, was more than disappointed over the condition of the park and took action. In January of 1987, he formally requested that the city transfer ownership of the park to Millcreek Township, and city council approved.

After some back and forth negotiation regarding mineral rights, rights to build a water tower, and ensuring that city residents would be able to use the park, it was signed over to Millcreek Township in July of 1987. In December, C.F. Zuck praised Millcreek for taking over ownership of the park, stating that he knew his granduncle would be pleased.

The new deed was subject to all the original covenants and restrictions except as modified by any of the new deed’s covenants. The city would have the right to erect a water tower on Zuck Park property, if needed. The city retained the mineral rights, but they would be subject to Millcreek’s approval. Millcreek agreed to “maintain the property as a public park for use of any and all residents of the City of Erie, the Township of Millcreek or any other persons who wish to use such facilities.”

According to Millcreek leaders, Zuck Park was a mess, unkempt and damaged by vandals. Restrooms were inoperable. Millcreek Township allocated $13,000 for park improvements in its 1988 budget. When they inquired about having the playground equipment restored to the park, Mayor Tullio responded that it was not part of the deal.

By July of 1988, the park was ready to open once again. Picnic tables and cooking grills were restored. The restrooms and drinking fountain had been repaired. A new picnic pavilion had been constructed. Playground equipment was on the way, and the gates would remain open 24 hours a day so the police could patrol the area.

Zuck Park Today

In an effort to raise funds for its parks system, in 2006, Millcreek sought bids from lumber companies to cut dead, diseased, and healthy trees from the park. This was not without resistance with some of the citizens of Millcreek. While it was argued that falling and dying trees were hazardous to the public, of the 233 cherry, oak, maple, and tulip poplar trees removed, 116 of them were healthy. The township made $8,850 from the deal, and dozens of stumps from healthy trees lie visible beneath the Zuck Park canopy years later.

Despite its history of attention and inattention, Zuck Park prevails under the care of Millcreek Township. The eastern section of the 20-acre park features a baseball/softball field, tennis courts, a picnic pavilion, and a playground. The west side contains a shelter with three rows of picnic tables and a cooking grill. Visitors can enjoy nice playground features, including swings, a climbing apparatus, and a sliding board. Parents can keep an eye on their kids from one of the nearby benches. There’s even a bench glider that accommodates several people at a time. Between the two sections of developed park, three east/west paths run through the woods.

If you go, it might be difficult to tell where Zuck Park ends and the Zem Zem Temple property to its north begins. The boundary is just north of the ball field at the east end of the park and just south of Hammocks Drive across Zuck Road on the west end.

Another subtle demarcation of the north property line is the difference in the maturity of the trees. The mature park trees are the result of several planting efforts over the last century while the Zem Zem property was farmland and tree growth occurred naturally over time.

The north side of the park is forest and nearly impossible to get through during the summer, due to underbrush and pricker bushes. If you do venture into the woods, you’ll find relics of past recreation, including old picnic tables and a cleared area with white boulders arranged in arcs. Nearby is a marker on the ground with the inscription, “Northumberland.” A similar marker is located at the eastern entrance to one of the cross-park paths. It’s inscription reads, “Maiden Lane.” It would be interesting to know the history associated with those relics.

Zuck Park could use some manicuring and maintenance, but future plans for the park should be made with the knowledge that it is not just humans who use it. It’s still a haven for wildlife and should continue to be so. Zuck Park was a gift to all. A gift that is steeped in history and a promise for the future.

Source: Erie Daily Times, Erie Times-News, and Erie Morning News accessed through Erie County Library and NewsBank

Back in the early 60’s several of my neighborhood ‘buddies’, and I would have my mom drop us off, after school, on Grandview (just east of Zuck Park), along with a couple of my dad’s Beagles, and we would hunt all the way north, east of Zuck Rd. and across 38th St and onto the (then Palermo Farm, the current site of a subdivision, I can’t remember the name.) ending up in the playground of Ridgefield School. There were wild Ring Neck Pheasants and rabbits. Great memories of living in Millcreek.

I would have turned six in the summer of 1974, when the new “elaborate” slide, metal merry-go-round, and picnic tables with grills were installed. Sure enough, I remember my mother taking my younger brother and I there to play and have a picnic lunch or snacks. It was a big event when we got to go to Zuck Park! I remember how much we enjoyed the playground and I think my mom enjoyed sitting in the shade and watching us run around. We were residents of West Millcreek who had only a limited number of places we could go, within a 10-minute drive, that would offer such opportunities. Zuck Park holds an affectionate place in my heart because of these fun and special times spent there in my childhood.

I grew up just down the street from the park in the 70 & 80’s. My friends and I loved the park, trails and the 2 ponds that were there. Who could ever forget that awesome slide, monkey bars, swings, and those animals with the heavy springs to rock on. It’s a shame the ponds are gone and it still needs cared for better. I remember the field trips from school (OLP) up to the park. Would like to see those things come back again.

Very interesting, Ann. I’ve often wondered about the various structures there as I wandered around with the grandkids. We have released a bunch of chipmunks there over the years.

Another great chapter in your blog, Ann! Since Zuck Park is near our home, I enjoyed taking my granddaughter there numerous times from about 2003 to 2012. I remember some geocaching going on there too.

Ah, what a lovely memory!

Now I know! Often wondered about the origins and current status of Zuck Park. Thank you, Ann.

Just a theory on the markers…. In Northern England, “Maiden’s Way” is a Roman Era road that leads to a section of Hadrian’s Wall (white boulders?) which happens to be in Northumberland County.

Quite possibly!