Dimorier Project: Prologue

Purchase William E. Dimorier: Servant Leader

Prologue

Brilliant reflections of the early sun pierced the century-old glass of my office window, in a room once slept in by house servants. On the third floor of an 1893 brick mansion, now Gannon University’s Old Main, I pulled out the draft of a grant proposal and started to read.

I heard a tap on the heavy wooden door, and looked up to see my colleague, who proposed a lunchtime excursion to an auction preview at the AKD Printing Company, which was liquidating its business. The advertisement noted prints of paintings by her late uncle, Joseph Plavcan, a well-known artist in the area. After one of northwest Pennsylvania’s snowiest winters ever, the day’s pleasant weather called for a walk, so I agreed, unaware of the life-changing discovery that awaited.

A few hours later, several of us from the university’s development office strolled five blocks south to the ivy-draped, red-brick building that once housed a thriving printing company. Just inside, the dim and silent cavernous room hosted scores of relic-like machines that squatted on the dusty floor constructed from interlocking wooden blocks.

Where were the prints? A white-haired wizened man, no more than five feet tall, advised us that we’d find them on the second floor.

Steep narrow steps opened to an office walled with shelves of various-sized paper. In the center of that room stood a massive, counter-height cabinet, and on it lay a stack of prints that Carol recognized as Plavcans. All of the sheets depicted the same scene in each of the basic inks for four-color printing, yellow, magenta, cyan, and black, in addition to a few complete versions.

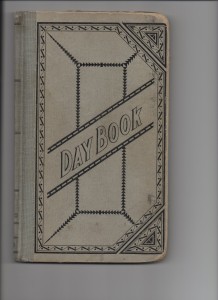

As my colleagues assessed the prints, I wandered into another room and down an aisle of varied inventory until I ran my fingers across a stack of old books sitting among others on an expansive table. At the top of the pile sat a moss-green journal, five by nine inches, a black, art-deco design on the cloth cover, and the title, “Day Book.” Inside, someone had written, “This book belongs to W. E. ——,” the surname illegible. Skimming through the pages, I found poem after poem, handwritten in fountain pen, exploring a variety of subjects, including the wind and the sea. The fact that several versions of a poem appeared indicated that these were originals. The verses were loaded with sophisticated literary devices, classical references, and many of them explored unusual topics, including the following poem about steel.

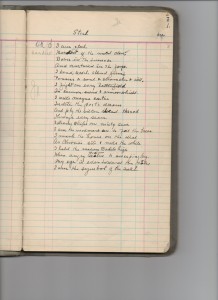

Steel I am steel, Hardiest of the metal clan, Born in the furnace And nurtured in the forge. I bend, recoil, stand firm, Possess a soul & character & will. I fight on every battlefield In cannon, sword & armor-shield. I write magna cartas. Indite the poet’s dream And ply the silken thread Through every seam. I steady ships on misty seas, I am the woodman’s ax to fell the trees. I mark the hours on the dial As Chronos sits & nods the while. I hold the modern Babels high When angry Aeolus is sweeping by. My eye is ever toward the pole, I am the symbol of the soul.

A page from William E. Dimorier’s poetry journal.

The words, “Born in the furnace” and “bend, recoil, stand firm,” suggested an author with some knowledge of the steel-making process, yet steel is personified in this poem. In addition, the classical references indicated an appreciation for history, philosophy, mythology, religion, and literature. In spite of the incongruity, I assumed the poet was a woman. But, who was she?

There were dates written under some of the poems, with the oldest being July 19, 1937, nearly sixty-seven years before I stood there in the printing house. The poet could still be alive if she had written them as a young woman, but it was unlikely.

Had these poems ever been published? Why else would the journal be left at a printing house? But why hadn’t it been returned to its owner? Perhaps it was actually the property of a lonely AKD Printing clerk, who had long ago left the company. Many thoughts were coming to me in a rush, and I decided I had to have the journal for my own so I could solve the mystery.

A dark-haired man pulled up beside me. He was almost as small as the white-haired man who had directed us upstairs, which made sense after I learned they were father and son. I asked the younger man if I could buy the journal that day, and he informed me that I’d have to attend the auction just like everyone else, as if I thought I was deserving of special treatment. I made it clear to him that I had no idea how auctions worked, and my only experience originated in childhood with a livestock auction I had attended with a country cousin.

“Well then, here’s how it goes,” he said. “You come on Saturday and get a number. Then, you bid and pay me lots of money. Of course, I’ll take a check, if it’s good.”

The man’s short and snappy tutorial didn’t instill much confidence in me. How much money was “lots?” Because it was only Tuesday, I had plenty of time to ponder that question. I spent a significant amount of energy fretting that someone else would discover the journal and outbid me at the auction. I tried to sooth my worries by reasoning that if someone else wanted it that badly, they would probably take good care of it.

The difference, I thought, was that I might be able to transcribe the poems and have them republished. Then, whoever had written them would have her work recognized instead of having it confined to a shelf in someone’s bookcase and later tossed in an attic box or thrown in the trash.

The Auction Acquisition

Saturday morning finally arrived, and I ushered my husband to the second floor of the aged building, so I could show him the journal. As we started down the aisle, we saw a woman standing in front of the table where I had made my discovery a few days before. As she leafed through its pages, she marveled to another woman standing near her that it was filled with poetry. Fears now manifested, it seemed sure we would be facing a fierce competitor. We had decided that the maximum we could afford was $150, and I worried that the bidding could actually reach into the hundreds or thousands of dollars.

The auctioneer began the sale on the third floor, where he offered all of its contents, and finally the building itself, before leading everyone down the stairs, where the Day Book awaited its fate. It seemed like he called everything in the room before moving to the parcel of old ledgers and books topped by the poet’s journal. I was delighted when he opened the bid at only five dollars and dismayed when the woman whom I had found touching my treasure raised her hand.

My colleague, whose proposition a few days earlier had launched this adventure, had also advised me not to bid right away, so as not to appear desperate and drive up the price. She said to wait until the bidding paused, and that didn’t take long. When no one else took the $7.50 prompt, I jumped in and braced myself, waiting to see what the other woman did. Moments passed in silence. Going, going, gone. The stack of books, including the poetry journal, was mine.

Since my husband and I were situated on the opposite side of the table from where the auctioneer and my opponent stood in front of the parcel I’d just won, I’d have to reach across to retrieve my prize. Still not wanting to reveal my desperation, I decided to wait for the group to move along. First, though, the auctioneer plucked the journal from the pile.

“You’d better take this. If it gets lost, you’ll be heartbroken,” he said as he started to hand the journal to me.

Before our reach could meet, however, the first bidder intercepted.

“Do you want this book? It contains handwritten poetry!” she said to me, waving the journal around.

“Yes, I know,” I said, and as I retrieved it from her grasp, my eyes warning, “Back off, woman.”

She mumbled and moved along. The auctioneer lifted his eyebrows and smiled at me, and the other bidders, as witnesses, registered amusement.

As I paged through the journal in the car on our way home, I told Jim I thought perhaps I was meant to have it all along. We had been prepared to spend $150, prepared to lose the bid if it went higher than that, and astounded when the journal became ours for only $7.50. With this good fortune came the weight of responsibility. Now, I had to find out my poet’s identity.

The Work Begins

On Monday morning, I brought the Day Book to work, and my boss at the time, who was director of research at the university, started digging into the mystery of the poet’s identity, whom we both assumed was a woman. Later in the day, she walked into my office and said, “Your poet isn’t a woman. He’s a man, William Edward Dimorier, and he was once the assistant principal of Academy High School.”

With that kernel, the Dimorier Project was launched. William would become a part of my life, as much as if he were a living and breathing member of my family. He would also come to be known, to many who know me, as “my dead poet.”

Because William Dimorier was not a famous person, putting together the story of his life was quite a challenge, however, as digitization of resources expanded over the years, his portrait began to fill in. Therefore, William’s biography, written more than a decade after I acquired his poetry journal, is much richer than if it had been completed in a “timely fashion.”

In addition to digitized Internet sources, I scoured more than eight decades worth of microfilmed newspapers, many of which came from the New York Library System through interlibrary loan. There were also primary sources, including personnel records from the Erie School District and documents donated to the Afton Museum, in William’s hometown, by the wife of William’s nephew, Dorotha More Wood.

Dorotha More Wood, wife of Gordon Wood, son of William’s sister Mary, donated small artifacts, correspondence, diaries, and books from William’s personal library, which he had bequeathed to Gordon, to the Afton Museum. In 2013, the museum staff was cleaning house and needed to part with some of the many books in their inventory because of space issues. Charles Decker, the Afton historian, with whom I had consulted many times, noticed William’s signature in 10 of those books and offered them to me. I eagerly accepted them. Mr. Decker, and countless other individuals, have proven to be treasured resources for the Dimorier Project.

As the years wore on since acquiring William’s journal, the project stopped and started many times, resulting in research redundancies and errors. I realized that it would never be completed at its current pace, considering the growing mass of physical and electronic research materials and the limited amount of time available for the project. Something had to give.

Committing to the Dimorier Project

In 2013, the Dimorier Project nagged at me daily. Every activity seemed to steal time away from my dead poet. I greatly enjoyed my position as a program director at Penn State, but it became clear that while I was helping our students realize their dreams, I was neglecting my own. So, in the summer of 2013, I gave my notice, and at the end of September, I said goodbye to one life and hello to another, fortunate to have the financial and emotional support of my husband, Jim, who has proven to be my champion and hero.

Faced with nearly a decade of research materials, I spent the fall of 2013 organizing piles of paper and hundreds of computer files and emails. The winter of 2014 was spent at the Erie School District administration building, paging through personnel file and school board minutes. This was followed by months spent in the Heritage Room at the Erie County Library, viewing high school yearbooks and newspaper microfilm. I became such a fixture that one of the staff members joked that I should have my own office.

The data on William Dimorier soon doubled in size, but it was now housed in a more-organized fashion. I could have kept going and going with my research, but at some point, I needed to produce a product, so I started writing. From all of the data I had collected, approximately half was used for the first draft of a chronological biography.

The second edit struck out paragraphs of information not essential to the story of William’s life, and through this edit, I sought my thesis. What made William’s story of value to others? Once the second draft was complete, the picture became clear. Connections had made, and epiphanies were realized. A thesis statement was born.

Service to others is worthwhile, even if unrecognized.

Discovering the Servant Leader

The third draft resulted from an edit that dissected every paragraph to tell an interesting story, relate it to the thesis, and inform the final chapter. The fourth draft mercilessly cut the fat and tightened the verbiage. The fifth tells the story of a man who led a life of service, which went largely unrecognized, but proved to have an influence that stretches around the globe and across centuries, and from which, we can all learn that reward does not always make a life meaningful. William’s life fits closely that described by Robert K. Greenleaf as a servant-leader, one who starts with the desire to serve and becomes a leader, rather than the opposite path.[1] Although William E. Dimorier was a humble man and never expected much recognition, readers of his biography may agree that such a gesture would be well deserved.

Finished Product

After careful attention by a professional editor, William E. Dimorier: Servant Leader is now available for purchase. Here’s how to order a copy of William E. Dimorier: Servant Leader.

–Ann Silverthorn

NOTE:

[1] Robert K. Greenleaf, “The Servant as Leader,” The Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, 1970.

Leave a Reply